Six Timeless Tales for Managers of Modern Buildings

• •

Inspired by Aesop • Written for Institutional Building Managers & Maintenance Engineers

A Guide for Building Stewards

Proactive Maintenance • Structural Integrity • Long-Term Value

For Institutional Facilities Professionals

A Foreword to the Reader

Twenty-six centuries ago, a Greek storyteller named Aesop understood that the most powerful lessons are the ones wrapped in a good story. He knew that people remember the tortoise and the hare long after they forget the lecture about planning ahead.

The following six fables are written in that ancient tradition. The characters are ants and spiders, beetles and bees, crickets and tortoises. Their struggles are small—a cracked log, a leaking hive, a flooded burrow. But if you have ever managed a building, you will recognize every one of them. The scale changes. The lesson does not.

These stories are for the people who walk the hallways before anyone else arrives, who notice what others step over, and who understand that the work no one sees is the work that keeps everything standing.

- • •

Fable I

The Two Colonies

Two meadows, Two ways

Two colonies of ants lived beneath the same meadow, separated by a stone’s throw of earth. Their tunnels were deep, their chambers well-stocked, and their queens content.

In the first colony, an old worker named Maren had a habit the younger ants found tedious. Each morning, before the foraging began, she walked the full length of every tunnel. She pressed her antennae to the walls, tapped the ceilings, and noted where the soil was damp, where the roots had shifted, where a grain of sand had fallen loose overnight. When she found something amiss, she reported it to the diggers, who shored up the weak spot before the day’s traffic began.

“You waste half the morning on walls that are standing just fine,” the younger ants complained.

“They are standing just fine,” said Maren, “because I walk them every morning.”

In the second colony, no one walked the tunnels. The ants were industrious and fast—they hauled food, built new chambers, expanded deeper into the earth. Inspections, they believed, were the work of idle hands. If a tunnel held yesterday, it would hold today.

When the Rain Comes

When the autumn rains came, they came hard. Water pressed into the soil from every direction. In Maren’s colony, the trouble spots had been reinforced weeks earlier. The tunnels flexed but held. Some drainage channels, dug where Maren had noted persistent dampness, carried the water safely past the brood chambers. The colony lost nothing.

In the second colony, a section of tunnel that had been softening for months gave way without warning. The collapse blocked the main passage, flooded the food stores, and trapped a hundred workers in a lower chamber for two days before they could dig themselves free. The colony survived, but barely, and they spent the rest of autumn rebuilding what the rain had taken—work they could not afford with winter approaching.

A scout from the second colony, visiting Maren’s tunnels to trade for seed, marveled at how dry and sound they were. “You were lucky,” she said.

Maren smiled. “Luck,” she said, “looks a great deal like paying attention.”

♦

The Moral:

The walls that never fall are not the walls that were built strongest. They are the walls that someone walked past every morning and checked for cracks, dampness, and shifting—before the rain made the decision for them.

Fable II

The Spider and the Swallow

The Web and the Nest

A spider named Orla built her web in the corner of a barn’s eave, where the beams met the roof and the wind could not easily reach. It was a fine web—symmetrical, strong, and perfectly placed to catch the evening gnats that drifted up from the pasture.

Each morning, before the dew had dried, Orla walked every strand. She mended the small tears left by the night’s catches, tightened the anchor lines, and replaced any thread that had lost its elasticity. It was quiet, unglamorous work, and it took nearly an hour each day.

A swallow who nested in the same barn watched this ritual with amusement. “Why do you fuss so?” the swallow asked. “Your web is already built. You could be resting. You could be eating. Instead, you spend every morning fixing what isn’t broken.”

“It isn’t broken yet,” said Orla. “That is rather the point.”

The swallow shook her head and flew off to hunt. Her own nest, she noted proudly, had been built in the spring and hadn’t needed a single repair since.

The Storm

In late summer, a heavy storm blew through the valley. The wind shook the barn and drove rain sideways through the eaves. Orla’s web, taut and freshly mended, bowed and flexed but held firm. When the storm passed, she had lost only a few outer strands, which she repaired before noon.

The swallow’s nest, which had quietly been loosening at its base for weeks—mud drying, straw slipping, the weight of four grown chicks pressing on joints that no one had thought to reinforce—tore free from the beam and fell. The chicks, thankfully, could already fly, but the nest was destroyed entirely. The swallow spent three exhausting days building a new one from nothing, in weather far less forgiving than the spring in which she had built the first.

Orla, from her corner, said nothing. She was too busy mending a thread.

♦

The Moral:

A small repair each morning prevents a total rebuild after the storm. The joint that loosens, the seal that dries, the fastener that rusts—none of them will wait for a convenient time to fail. Maintenance is not the work you do when something breaks. It is the work that keeps it from breaking.

Fable III

The Beetle and the Beautiful Garden

Above and Below

A dung beetle and a butterfly both lived in a grand garden tended by a meticulous gardener. The butterfly spent her days among the roses and the lilies, admiring their colors and savoring their nectar. She was the envy of every insect in the garden, for she lived among beauty and wanted for nothing.

The dung beetle, meanwhile, worked below. He tunneled through the soil, turning and aerating the earth, burying organic matter deep where the roots could reach it. His work was invisible, thankless, and—the butterfly never tired of saying—beneath her.

“You spend your life in the dirt,” she said, “while I dance among the petals. What is the purpose of all your digging?”

“The petals,” said the beetle.

The butterfly laughed and flew away.

The Summer Without the Gardener

That summer, the gardener fell ill and could not tend his beds. No one watered from above. No one added compost. The weeks wore on, and the garden began to suffer. Flowers wilted. Leaves yellowed. Roots, starving for nutrients, curled inward.

But in the corner of the garden where the beetle had worked most diligently, the soil held its moisture longer. Channels he had dug allowed the rare rains to penetrate deep, and organic matter he had buried slowly released its richness to the roots above. His roses were the last to fade, and the first to recover when the gardener finally returned.

The butterfly’s favorite lilies—planted in soil that was compacted, shallow, and untended beneath the surface—were the first to die. She had admired them every day but never once considered what held them up.

When the garden recovered, the butterfly alighted near the beetle’s mound of earth. “I never understood your work,” she admitted.

“Most don’t,” said the beetle, and went back underground.

♦

The Moral:

What is beautiful above depends entirely on what is tended below. The lobby gleams, the tenants are happy, the inspectors pass—and no one thinks to ask what is happening underneath, in the dark, where the roots draw their strength. Until the day it stops holding.

Fable IV

The Crickets in the Log

A Pinch of Dust

Two crickets found shelter in a fallen oak log at the edge of a forest. The log was thick, dry, and hollow enough for comfort—a fine home for a cricket. They settled in at opposite ends and lived well through the spring.

By early summer, the first cricket—a careful fellow named Pell—noticed small piles of sawdust near his chamber. He investigated and found that powder post beetles had begun boring into the heartwood nearby. The damage was small—barely a pinch of dust—but Pell knew what it meant. He packed his things and moved to a sound section of the log farther from the beetles’ work, reinforcing his new chamber with woven grass and dried resin to seal out moisture that might invite more decay.

The second cricket, Rinn, noticed the same sawdust near his end but shrugged. “A few beetles,” he said. “This log has stood for years. A little dust means nothing.” He swept the sawdust away and went back to singing.

Each week, Pell checked on the beetles’ progress. Each week, there was a little more dust. He mentioned it to Rinn during their evening conversations. Rinn always had the same answer: “It’s a big log.”

The Collapse

By autumn, the beetles had honeycombed the wood around Rinn’s chamber. One cool night, when the first frost made the wood contract, the section gave way. The ceiling of Rinn’s chamber collapsed—not with a dramatic crash, but with a slow, groaning sag that pinned him under a mat of rotting wood and frass. He escaped, but his home was gone, his food stores buried, and winter was three weeks away.

Rinn moved in with Pell, who had enough room and enough food because he had planned for exactly this kind of trouble. They sat together in the sealed, dry chamber and listened to the wind.

“How did you know?” Rinn asked.

“I didn’t know,” said Pell. “I just didn’t ignore what the sawdust was telling me.”

♦

The Moral:

Small signs of deterioration are not small problems. They are large problems announcing themselves quietly—a stain on a ceiling tile, a hairline crack that wasn’t there last month, a door that no longer closes flush. The wise resident listens to what the dust is telling him. The comfortable one sweeps it away and goes back to singing.

Fable V

The Bees and the Crack in the Hive

A Hairline in the Heartwood

High in an old elm, a colony of honeybees had built a magnificent hive inside a hollow where a branch had long ago broken away. The cavity was spacious, the entrance was sheltered from rain, and the colony had thrived there for five seasons.

One spring, a worker named Brin noticed a thin crack forming along the bottom of the cavity, where the heartwood met a seam of bark. A faint draft leaked through—barely noticeable, but enough to carry a thread of outside air into the brood chamber, where the temperature had to be kept precise.

Brin brought the crack to the attention of the hive’s master builders. “We should seal it now with propolis,” she urged. “It will take an afternoon’s work. A small crew. A modest amount of resin.”

The master builders looked at the crack and looked at each other. “It’s a hairline,” they said. “We have nectar to store, comb to build, and a new queen to raise. We’ll seal it after the honey flow, when there’s time to spare.”

What the Crack Became

Summer passed. The honey flow came and went. The crack widened by a fraction no one measured. Rain found the opening and dampened the wood around it. The damp wood softened. The softened wood swelled and split further. By early autumn, what had been a hairline crack was a finger-width gap, and a persistent draft was cooling one side of the brood chamber. The bees on that side had to work twice as hard to maintain temperature, burning through honey stores at an alarming rate.

Now the master builders scrambled to seal the gap. But the wood around it was wet and soft—propolis would not adhere to it properly. They had to first dry the area, then pack it with wax, then layer propolis over the wax, then reinforce the surrounding wood to prevent further splitting. What would have been an afternoon’s work in the spring became a week’s work in the fall, done by bees who should have been preparing for winter.

The hive survived, but they entered the cold months with less honey and more fatigue than any year before. Brin said nothing to the master builders. She did not need to. They could feel it in the weight of the stores—or rather, in how little weight there was.

♦

The Moral:

A crack sealed in spring costs an afternoon. The same crack sealed in autumn costs a season. Water does not wait for your budget cycle. Corrosion does not pause for your staffing shortage. The work does not wait for you. You must go to it—or pay tenfold when it comes to you.

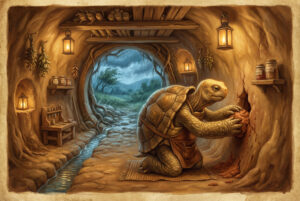

Fable VI

The Old Tortoise and the Young Hare

Two Burrows on a Hillside

An old tortoise and a young hare both tended burrows on the same hillside. The tortoise’s burrow was nothing remarkable to look at—a modest hole in the earth with a low entrance and plain dirt walls. But it was dry in every season, cool in summer, warm in winter, and had never once flooded in the forty years the tortoise had lived there.

The hare’s burrow was new and impressive. He had dug it deep and wide, with multiple chambers, a ventilation shaft, and a cleverly angled entrance that caught the morning sun. The other animals admired it. The hare was proud.

One evening, the hare visited the tortoise and looked around the plain little burrow with barely concealed pity. “No offense, old-timer,” he said, “but this place is rather basic. No ventilation shaft? No separate sleeping chamber? Haven’t you ever thought about upgrading?”

The tortoise looked up slowly. “Every year,” he said, “I dig a small drainage channel along the uphill side and clear the old one of roots and debris. Then I pack fresh clay into the walls where the frost has loosened them, and check the ceiling for root intrusion, trimming anything that might hold moisture. I have done it every spring for forty years. It takes me three days each time.”

“That’s a hundred and twenty days of your life spent maintaining a hole in the ground,” the hare calculated.

“Yes,” said the tortoise. “And I have spent zero days rebuilding one.”

The Snowmelt

The next spring brought unusually heavy snowmelt. Water poured down the hillside and found every burrow. The tortoise’s drainage channel—freshly cleared, as it had been every year—carried the water safely past his entrance. Inside, the clay-packed walls shed moisture like a duck’s back. He slept through the worst of it.

The hare’s impressive burrow, with its deep chambers and many passages, had no drainage to speak of. Water poured in through the ventilation shaft he had been so proud of. It pooled in the low-lying sleeping chamber. The cleverly angled entrance, which caught the morning sun so nicely, also caught the morning runoff. By dawn, the hare was standing in his entrance, soaked, watching his burrow fill with muddy water.

He rebuilt it that summer—bigger, deeper, more impressive than before. But he added no drainage channel, and he did not pack the walls with clay.

The tortoise, passing by, said nothing. He knew they would have this conversation again.

♦

The Moral:

A modest home well-maintained will outlast a palace that is only admired. New finishes, upgraded lobbies, and modern fixtures mean nothing if the envelope leaks, the drainage fails, and no one has checked the grade in years. It is not the grandness of what you build that matters, but the faithfulness with which you tend it.

Epilogue: From Fable to Hallway

Of course, these fables belong to the meadow, the garden, the forest, and the hillside. But if you have spent your career inside the walls of a building — walking its corridors, checking its systems, worrying over its cracks and its dampness and its age — you will have recognized yourself in these pages.

After all, you are Maren, walking the tunnels each morning. Orla, mending the web before the storm. The beetle, doing the thankless work beneath the surface. Similarly, you are Pell, reading the sawdust, and Brin, urging action while the crack is still small. Above all, you are the old tortoise, packing clay for the fortieth spring.

Or perhaps, on some days, you have been the others. The swallow who assumed the nest would hold, a butterfly who never looked beneath the petals, a hare who mistook grandness for soundness. In truth, we have all been both characters in every fable at one time or another.

However, the difference between the two is never talent, or budget, or luck. Instead, it is attention. It is the willingness to look at what is small and unglamorous and ask: what is this becoming? And then to act while the answer is still cheap.

Ultimately, the repair you need today will always cost less than the emergency you’ll face tomorrow. Every creature in these fables learned that lesson. Without exception, the wise ones learned it early.

When Diligence Alone Is Not Enough

And yet, even the most diligent steward eventually meets a problem that exceeds the reach of routine care. The crack that runs deeper than expected. The settlement that will not stop on its own. The water that finds its way in no matter what you seal. In those moments, the wisest thing a building keeper can do is exactly what Maren, and Pell, and the old tortoise would have done — recognize the limit of what daily attention can solve, and call someone whose life’s work is solving what comes next.

For that reason, Foundation Tech, Inc. has spent decades doing just that — stabilizing, repairing, and restoring the structures that good people work hard to maintain. When your diligence has done all it can, and the problem asks for more, they are a phone call away.

Foundation Tech, Inc. • www.foundationtechinc.com • (661) 294-1313 • Toll Free: (855) 650-2211

Be the tortoise. Be the ant. Be the beetle.

Walk the tunnels. Mend the web. Pack the clay.